While the printing press revolutionized one half of the world, it left another struggling to adapt.

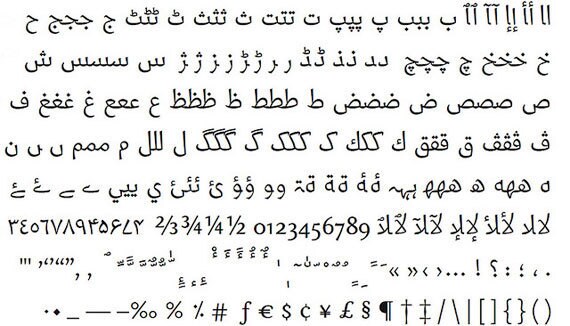

In a recent heart-warming story that came out of of Beijing, Chui Xianren, a homeless man who had been badly injured in a fire, gained widespread popularity after pictures of his street art appeared online. His handwritten Chinese characters were so captivating, a tech company hired him to develop a new font that will be named after the artist. "Chui’s writing is quaint and elegant. It is so beautiful that we believe that with some development it will be widely used in advertisements," said the product manager of Founder Electronics. China, like so many other developing nations, is starved for new typefaces. In the Western world, where the printing press was invented, Times New Roman is the accepted font for newspapers due to its dependable legibility. Yet for the rest of the world that relies on calligraphic script, creating standardized, nationally recognized fonts is an incredible challenge. In the Arabic world, for example, literacy has only gotten worse in the past 50 years, which some argue is due to underdeveloped typefaces that can't articulate the complexities of script. When Gutenberg developed the printing press in the 15th century, he was working with Europe in mind. The printing press was not designed to address the complexities of non-Latin based fonts, causing much of the world to struggle to keep up with the technology of movable type. While Latin-based fonts emphasize verticality with ascenders and descenders, Arab fonts expand and are linked horizontally. Even more, the 28 basic letter forms in the Arabic alphabet take on different physical features depending on where they are positioned within a word.

Through the 20th century, several font designers came forward to address the lack of development in the printed from of Arabic. The situation improved in 1993, when Mourad Boutros created a set of Arabic fonts for computers. To achieve such a feat, Boutros promoted "Basic Arabic," a simplification of the written language. Though his work pushed the Arab world into the literary future, much of the rich nuance of the written language was lost. Yet the step was crucial — while Westerners benefit from hundreds of preinstalled fonts on their computers, the Arab world only receives two.

Now, the Arab world is faced with two options: reinvent the printing process or simplify the language. While many are championing the latter choice, they are met with opposition from those who fear that Westernizing the language will destroy its calligraphic nature, and ultimately, a piece of cultural heritage. Yet in some ways, simplifying the alphabet might be similar to the Western move away from what we now call Blackletter typefaces, the beautiful, handwritten lettering of manuscripts that dominated Europe's finest manuscripts until the invention of the printing press. While this debate continues, many citizens are creating their own forms of typography. "The lack of specialists and variety in available typefaces left the door open for experimentation at the end-user level," writes Nadine Chahine, an Arabic type design teacher at the American University of Dubai. "The result is the Frankenstein of Arabic typography, cut up pieces of decent Latin typefaces put together to make up Arabic characters." Fortunately, many young designers are hard at work in areas like Lebanon and China, developing their country's own version of Times New Roman. Technology may solve many problems, but it depends upon your perspective — while the printing press revolutionized one half of the world, it left another struggling to adapt. Hopefully a compromise will be found, protecting the history of such artfully written languages, while creating a legible font that is able to widely convey said cultural heritage.