I’ve always had a thing for pearls. They’re my birthstone, for one. I wore a single, round, Japanese pearl around my neck the day I got married. I even have a dog named Pearl. So when I learned that my neighbor Stephen Bloom had written a book about pearls, I wanted to learn more.

I’ve always had a thing for pearls. They’re my birthstone, for one. I wore a single, round, Japanese pearl around my neck the day I got married. I even have a dog named Pearl. So when I learned that my neighbor Stephen Bloom had written a book about pearls, I wanted to learn more.

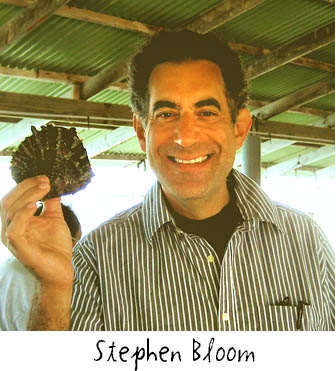

Steve is a journalism professor at the University of Iowa and I met him in his office, lined with the books and file cabinets typical of an academic. His professorial nonchalance altered, however, as soon we started talking about pearls. His voice rose, he leaned forward in his seat, he pulled out a manila folder in which a plastic grocery bag held fake pearls, an oyster shell from Japan, a gleaming, polished pearl shell from Tahiti, and a pair of tweezers used to sort pearls. He even asked to see the strand of pearls I was wearing.

Like me, Steve’s had a thing for pearls since childhood. He has memories of watching his dad help his mom with the clasp on her pearls as they dressed for a special occasion. A lot of us remember moments like that, but they don’t lead to a four-year, 30,000 mile journey. The history of pearls, as well as Steve’s attempt to trace a pearl from the floor of the ocean to the neck of a woman, and the characters he met along the way, is chronicled in Tears of Mermaids: The Secret Story of Pearls. I sat down with Steve to talk and share a peek of his findings with you.

Like me, Steve’s had a thing for pearls since childhood. He has memories of watching his dad help his mom with the clasp on her pearls as they dressed for a special occasion. A lot of us remember moments like that, but they don’t lead to a four-year, 30,000 mile journey. The history of pearls, as well as Steve’s attempt to trace a pearl from the floor of the ocean to the neck of a woman, and the characters he met along the way, is chronicled in Tears of Mermaids: The Secret Story of Pearls. I sat down with Steve to talk and share a peek of his findings with you.

Tell us a little about how pearls come into being.

Many people think that a pearl is created when a piece of sand gets into an oyster, but this isn’t true. Real pearls grow in oysters and mussels, which are incredibly adept at filtering sand out of their systems. What happens is that a tiny piece of coral or an unfortunate tiny living organism attaches itself to the meat of the oyster and, in order to protect itself from the irritation, the oyster covers the invader with layers of nacre, the smooth, luminous substance that makes up the pearl. Now this is how natural pearls are created, but it’s extremely rare to find a natural pearl.

Almost all pearls today are cultured or cultivated pearls. In oysters, they’re grown by inserting a small bead — which is made of a piece of clam shell from the Mississippi River Delta — and a piece of oyster tissue into the mollusk; in Chinese mussels there are no beads, just tissue inserted. The shells are returned to the water, turned regularly, and harvested. Oysters produce one pearl, like an egg and a yolk, while a mussel can produce as many as 60 pearls of all different shapes and colors.

Searching for Chinese seawater pearls

What parts of the world produce pearls?  China, Japan, Indonesia, Vietnam, French Polynesia, Australia, Mexico, and the Phillippines. Pearls from Japanese oysters made up the largest portion of the market for many years. In the 1970s, the Chinese started producing freshwater pearls in mussels, and today, 99% of freshwater pearls come from China. Most people involved in crafts use Chinese pearls. Freshwater pearls typically aren’t round, although as Chinese technology has improved, they are also producing round pearls and much larger pearls than those that could grow in Japanese oysters. Chinese pearls come in a variety of colors, and the Chinese also treat some of their pearls, using bleach or dyes.

China, Japan, Indonesia, Vietnam, French Polynesia, Australia, Mexico, and the Phillippines. Pearls from Japanese oysters made up the largest portion of the market for many years. In the 1970s, the Chinese started producing freshwater pearls in mussels, and today, 99% of freshwater pearls come from China. Most people involved in crafts use Chinese pearls. Freshwater pearls typically aren’t round, although as Chinese technology has improved, they are also producing round pearls and much larger pearls than those that could grow in Japanese oysters. Chinese pearls come in a variety of colors, and the Chinese also treat some of their pearls, using bleach or dyes.

The Philippines produce a gold pearl that is totally over-the-top magnificent. Australia produces some of the largest and loveliest pearls in the world off their northern coast. They’re not grown in hatcheries like they are in China and Japan, and harvesting them on the open sea can be dangerous work. Tahiti is known especially for its black pearls (on right).

How do you tell if a pearl is real?

If you rub it across your teeth, a real pearl will feel slightly gritty. Pearl dealers, however, prefer to rub them together — if they’re smooth, they’re fake, while the telltale grittiness means they’re real.

Pearls from Chinese freshwater mussels

How should you care for pearls?  Pearls are soft, and on a scale of zero to ten, with zero being talc and ten being diamonds, pearls are a three. So the old adage is “last on, first off" — when you get dressed, you put on your clothes and make-up and put on your pearls last and take them off first when you get undressed. Pearls will collect perfume and perspiration — you can even collect DNA off pearls. So you need to wipe them off regularly and they should be moistened a couple times a year with soap and water. They’ll wither if they’re left in a box or vault.

Pearls are soft, and on a scale of zero to ten, with zero being talc and ten being diamonds, pearls are a three. So the old adage is “last on, first off" — when you get dressed, you put on your clothes and make-up and put on your pearls last and take them off first when you get undressed. Pearls will collect perfume and perspiration — you can even collect DNA off pearls. So you need to wipe them off regularly and they should be moistened a couple times a year with soap and water. They’ll wither if they’re left in a box or vault.

What do you find so special about pearls?

Pearls reflect light, they’re organic, the way they come out of the shell is pretty much the way any craftsperson or jeweler will display them. You can’t change the shape of them like you can gold, for example, which you can mold to whatever shape you want, or diamonds, which are cut and faceted. Pearls are as close to natural adornment as it gets. They have a natural luminescence — they literally light up your face when you wear them.

Pearl and Lace Necklace by nyjolejewellery

No wonder we love them! You can learn more about Steve's quest to understand the journey of pearls in his book Tears of Mermaids: The Secret Story of Pearls, which is available at an independent bookseller or on Amazon.

A lifelong sewer/knitter and former weaver/spinner, Linzee Kull McCray, a.k.a. lkmccray, is a writer and editor living in Iowa. She feels fortunate to meet and write about people, from scientists to stitchers, who are passionate about their work. Her freelance writing appears in Quilts and More, Stitch, Fiberarts, American Patchwork and Quilting and more. For more textile musings, visit her blog.

Mother-of-Pearl Buttons Post | Process Articles

Browse Pearl Jewelry